Posted on 18 March 2022

Te Au o Te Moana – Voice of the Ocean: Lara Taylor

- News

- EBM in action Governance Kaitiakitanga Marine values Tikanga and mātauranga Māori Enabling ecosystem-based management

- 13 Minutes to read

Ko Te Arawa te Waka.

Ko Ohaki te Marae.

Ko Ngāti Tahu, Ngāti Whaoa te iwi.

Ko Lara Taylor ahau.

Our turangawaewae is at Ohaki, which is on the banks of the Waikato river near Taupō. I also whakapapa to Ngāti Kahungunu, to Ngāti Pahauwera but I don't know those connections very well, I'm just learning, our Hawkins whānau are from there.

Then we're also Ngāi Tahu down in the far south, Rakiura and right at the bottom of Te Waipounamu, but I don't know that very well either. So most of my time and connections are spent at Ohaki Marae and with my whānau there. That's on my mum's side. She's also Dutch, her dad came over on a ship from Holland. He was just a young man then. I never knew him though, he passed away before my nan. Mum grew up in Hawke's Bay, in Hastings. I grew up in Tāmaki Makaurau.

“Reconnect with their whakapapa and their place within Aotearoa…”

Tell me a little bit about yourself and your connection with Sustainable Seas? Why are you involved with Sustainable Seas?

My mum's mother, my Nan, committed suicide when I was a baby, or a couple of years old. There's always been kind of a... Well, there's a lot of mamae there in her family, and I guess for me growing up without her there and without that strong connection. That sense of disconnection and loss I think has had a big influence on me and the women on that side of the family. Intergenerational trauma that's rife throughout it. From my Nan and I'm sure, probably her nan's, and my female cousins and myself. I think that's affected who I am and why I do what I do.

The Māori research that I do, I'm wanting to help other people understand that disconnection and not really knowing your identity, having all these feelings of connection within yourself. You know, like my mum and her siblings and their aunts. You look at them and you know we’re Māori. I love looking at all the old photos on our whānau Facebook page too. People look at me and say, “are you? But you’re really fair for a Māori?” More than what I look like, it’s what I feel.

My mum's aunties I feel very connected to, and I love them, but I don't get to see them that much. I have memories of when I was younger and one of my great aunties made me a bone carving necklace, and it was such a special taonga to me. I want to help through my research other people to reconnect. Reconnect with themselves and their whakapapa and their place within Aotearoa and their connections to the environment as well, because I think that's all interconnected.

“…I want to help through my research, other people to reconnect. Reconnect with themselves and their whakapapa and their place within Aotearoa and their connections to the environment as well, because I think that's all interconnected.”

“Being able to breathe it and hear it and see it.”

How do you feel connected to the moana?

Growing up in Auckland, we've been surrounded by water all our life and on my dad's side, my nan bought a patch of land in Coromandel. So we've always grown up going down to Coromandel and just love the moana down there. Spent so much time fishing, surfing, so much time in the water. I’ve always had or been near views of water as well.

Where I live now I have a view of the ocean, the west coast. I almost feel like I can't live without a view of the ocean now. Being close to there and being able to breathe it and hear it and see it. But also, having that relationship with the Waikato awa and Lake Taupō. Knowing the connection as well from those maunga all the way down through the Waikato awa, out to the ocean, I think helps me to understand the interconnections between the different parts of the environment and nature, and respect for those.

“Helping people understand those interconnections.”

What motivates you to work for better moana management?

I have that interest for the moana and from a more scientific or environmental perspective, the “cumulative impacts” of all of our human activities on the land and going into our river and our catchments always end up in the moana. So by working with Sustainable Seas, I'm hoping that we can help people to understand those interconnections and that if we're doing work for Sustainable Seas and on the moana we're actually doing work for the entire environment and all of Aotearoa, because it's all interconnected.

Probably the biggest challenge I find is that we know that, and most of the people we work with know that. But then it comes down to reporting or producing outputs and things, and you're told you have to stay in your lane. I'm like, we've overcome that, but it's there's still that way of thinking sometimes.

I think ecosystem-based management (EBM) has been picked up as the focus for Sustainable Seas because it's a well-known approach that's used all around the world, so it's something that the Challenge could pick up and say, this is EBM. Everyone recognizes it, so it was probably that there weren't many other options for them, I don't know. It makes sense and it does have synergies with kaitiakitanga in Te Ao Māori, when you're thinking about the whole system functioning and being interconnected. The paper I'm working on at the moment with Dan [Hikuroa, who co-leads the Enabling Kaitiakitanga and EBM project with Lara] is looking at the concept of EBM. Kaitiakitanga as a philosophy or ideology can be alongside EBM sure, but then it's also so much more than that.

There are synergies, but there's differences as well.

“…if we're doing work for Sustainable Seas and on the moana we're actually doing work for the entire environment and all of Aotearoa, because it's all interconnected.”

“Evolving into something better, more holistic”

To you, what about the moana is worth protecting and saving?

The moana is a key part of who and what we are. We are water. We cannot survive without water. And the ocean may hold the greatest potential for dealing with the climate crisis. We need to look after our moana better if we expect the moana to protect and save us from our own demise, that’s reciprocity. So far, we’ve been just like the colonialists, not holding up our end of the bargain.

Whenever I visualise “Aotearoa-specific EBM” I always picture Papatūānuku, the islands – the forests and whenua are her korowai sheltering all the flora and fauna. The awa are her veins, and so on. She is embraced by Ranginui. The ocean is his salty tears. Together they provide balance and are the founding elements of a whole functioning ecosystem. This is just the picture in my head, it’s not necessarily ‘right’.

Te Korowai o Papatūānuku

So something I've been thinking about lately, and this is the simplified version, is that if we're enabling kaitiakitanga then there’s actually three key aspects that need to be enabled. We can’t just talk about ‘kaitiakitanga’. Operationalising kaitiakitanga requires the co-existence of rangatiratanga, mātauranga Māori, and tikanga Māori. But the current EBM concept with those 7 principles doesn't do those things. It includes co-governance partnership, Treaty partnership, but Rangatiratanga needs to be enabled within our own Māori spaces as well, not just in the partnership spaces with Crown and with wider community. We need to be changing our policy and legislation and practices, so that we're not impacting adversely on the practice of Rangatiratanga or the exercise of it, and mātauranga Māori and tikanga. We need to be enabling all three things if we are enabling kaitiakitanga.

The current ecosystem-based management concept, I think as according to the Challenge, it doesn't go far enough at all. So I'm really hoping that as the Challenge said at the start and they've published, this is a concept, it's a working concept, it's a work in progress. With all the research we're doing and all this thinking and solutions we're proposing, I'm hoping it will evolve into something way, way better. It's not called “ecosystem-based management”. I don't know what it's called yet, but it's much more holistic. And can actually provide for that dual sovereignty, I guess, or dual approaches.

“…We need to be changing our policy and legislation and practices, so that we're not impacting adversely on the practice of Rangatiratanga or the exercise of it, and mātauranga Māori and tikanga”.

“The moana is a part of who and what we are.”

What’s the biggest challenge you see in marine management?

The biggest challenge from my view is trying to get people to understand how interconnected all the systems and institutions are. Overcoming the barriers between different knowledge, knowledges, different policy and boundaries.

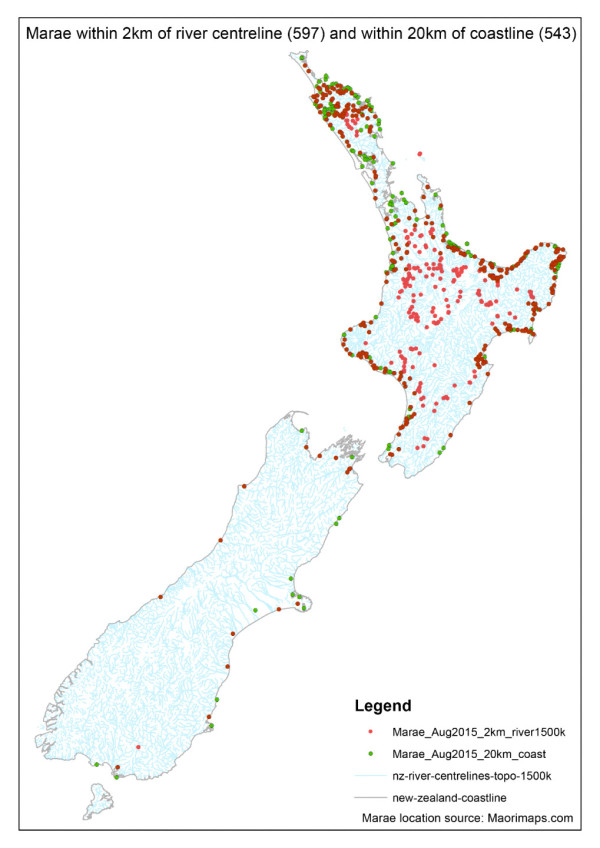

I think in terms of the challenges as well, is something around getting wider society and councils and things to really recognize the value and readiness of a lot of the marae around the coastline and up the rivers, and that we could really be optimizing marae based, sustainability and projects. That could be a real focal point that we could be putting a lot more energy and reconnecting wider communities, as well as obviously the whānau first to each other, but then the wider communities.

I've just got some vision around that.

“Imagine if we had marae-based initiatives, all the way from the mountains to the sea.”

What is one action New Zealanders can take to support the moana that aligns with your work at Sustainable Seas?

Imagine if we had marae-based initiatives all around Aotearoa, all connected, all the way from the mountains to the sea. It’s a ready-made network. If you look at the map of all the marae within a couple of kilometres of the coastline and the rivers, there are so many.

And that’s it, we could be really addressing a lot of the issues along our waterways and at the coast, through our marae and through our iwi and hapū and rūnanga possibly. Then those partnerships that are meant to be happening between Councils and iwi and hapū could be empowered through that sort of thing because it gives them a focus of something to work together on.

If the waterways are like the veins of Papatūānuku, then our marae are the capillaries that keep the blood circulating – keep the mauri flowing. Marae are hubs to restore and actually enhance the mana and the mauri of our wai – wai Māori, wai tai. Because only mana whenua can define mana, mauri or any other conceptual regulator. Mana whenua need to lead that, not councils or wider communities.

Councils and crown agencies need to really recognize and respect and learn from iwi and hapū and what they have to offer and the infrastructure and the marae itself and the processes that go on there, there’s so much to learn.

“…really recognize and respect and learn from iwi and hapū and what they have to offer and the infrastructure and the marae itself and the processes that go on there, there’s so much to learn.”

“Switched on whānau!”

How would you describe the current state of our moana in Aotearoa New Zealand?

It's so hard because I look out at it and it looks beautiful, but you know that it's not underneath the surface, you know things aren't healthy. I know through the science that it's reaching tipping point and our ecosystems are really messed up. I would describe the moana in a state of really needing our help and us to switch on. As humans, as people, to our responsibility for the moana and the impacts that we're having, the negative impacts we've had and our responsibility to fix that and regenerate it and enhance it.

There are places I don’t go because of the paru. Raw sewage during storms ruins a good stormy (surf). We have to be wary when we collect kaimoana – that it’s ‘safe’, and that it’s big enough, or that there’s even enough there to take any at all. A puppy literally died recently after jumping in a stream near us, that stream goes out to the moana. That’s not right. And we get excited when we see a big work-up and the birds going crazy from our house, or when a big fish is caught. We forget, and some of us don’t even know, what a healthy and flourishing moana actually looks like. I get frustrated because some people, lots of people, some of my family, choose to be ignorant. Easier that way. And they can continue doing what they do without taking any responsibility or going out of their way to change anything.

If we were to imagine the whenua as our earth mother and the ocean as our sky father, knowing that there is no real separation between the two and they’re totally entwined. Like the Whanganui River and Te Urewera Forest, recognised as ancestors of those iwi and given legal personhood, which the Crown and everybody’s been able to get their heads around. Would we treat our own mum and dad like that? Would we accept the state that they’re in and continue to turn a blind eye? I hope not – aue. I know I’ll be teaching my kids and moko one day to look after their tūpuna better than that.