Posted on 18 October 2023

Seafood Magazine: New 'ecosystem footprint’ research a big step toward collective action for healthy seas

- 7 Minutes to read

Shared with permission from Seafood New Zealand magazine - October 2023

Healthy marine ecosystems require an understanding of how ecosystems respond to stressors. With this understanding, marine managers, coastal communities, kaitiaki, blue economy businesses, and industry can prioritise actions that reduce degradation and restore the marine environment and fish stocks.

Until now, when people have tended to focus on individual stressors and their effects, rather than cumulative effects and an interconnected response. A new footprint framework from researchers at the Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge can help.

The ecosystem response footprint framework aims to help communities and environmental managers take a more holistic (ecosystem-based) approach to managing cumulative effects, and make effective decisions, even where detailed knowledge or data is not available.

Researcher Jasmine Low, based at the University of Auckland, says the framework is like a guideline or blueprint that aligns with ecosystem-based management and considers how whole ecosystems respond to multiple stressors or cumulative effects.

“It gives us ecological things to think about, the right questions to ask, and suggests collective actions to take.”

For example, marine managers and caretakers working to restore shellfish populations in a local estuary can use the framework to make informed decisions about the next best steps to take.

This includes identifying if the estuary is a viable location for shellfish recovery, and whether that recovery can naturally happen in a time frame acceptable to the local community. Or, if shellfish stocks from elsewhere need to be brought in and cultivated to reestablish lost populations.

By knowing where and when to take different environmental management actions, coastal communities and caretakers can actively reduce the risk of future degradation to coastal environments.

Footprints tell a story

An ecosystem-response footprint is a way of thinking about how an ecosystem reacts and changes in response to something that happens to it. Just as the different stressors on a shellfish population can combine, snowball, and reach tipping points, the way the ecosystem responds to restorative actions is also muti-faceted and connected. One size doesn’t fit all.

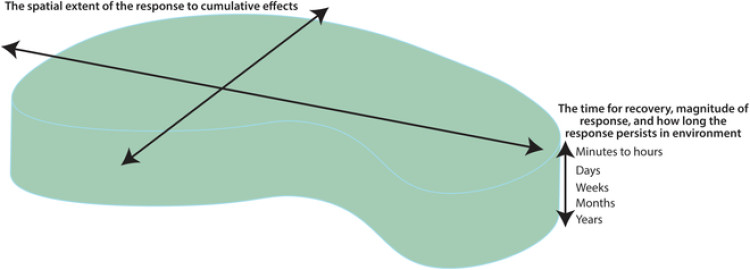

How an ecosystem responds and recovers from multiple stressors is like a footprint. It can be in one or more places, be a different length, width, and depth, and remain for different periods of time.

“We take this ecological information we already have and try and build an idea about how some stressors and their specific characteristics can affect the ecosystem — to generate different types of ecosystem responses.”

To define the size and depth of response footprints, researchers used the ecological principles of:

- legacy effects of stressors

- disturbance-recovery dynamics

- ecosystem interaction networks

- spatial and temporal scales of stressor regimes and ecosystem responses.

Conceptual footprint of the ecosystem’s response to multiple stressors, showing space and depth of the footprint.

Thinking about ecosystem response in this way, can help people make good decisions about marine management and use restorative resources in the most effective way.

“We can’t just base the way we manage marine environments on limit-setting approaches because the same thing doesn’t happen everywhere at the same time,” says Jasmine.

“For ecological recovery and resilience, we need a way of understanding all of the damage done to a particular marine ecosystem and the best management actions to take.”

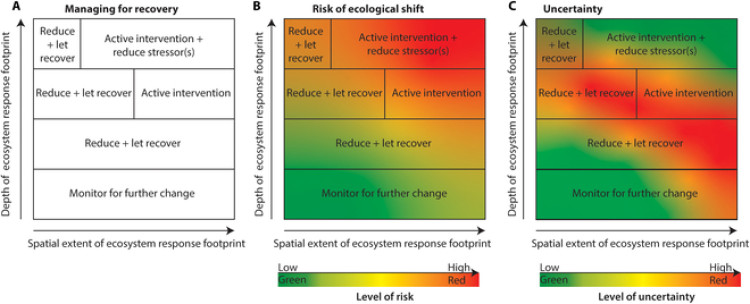

Each response footprint calls for a different management and conservation approach. For example, in situations when the response footprint is shallow, reducing the source of the stress can allow natural recovery to take place. But a deeper and larger footprint, might call for more active intervention in the recovery process for example, adding key ecosystem elements to assist natural recovery.

A: Summary of management actions likely needed to manage different types of response footprints.

B: The level of risk of poor ecological outcomes.

C: The uncertainty surrounding this risk.

Restoring estuary shellfish— a case study

A community wants to restore shellfish beds in their estuary within the next 10 years. To do this, different groups of people like kaitiaki, scientists, environmental managers, and communities need to understand certain things — how the cumulative effects of multiple stressors are happening, what the present and future ecosystem response footprints may be, and how these response footprints can alter the outcomes of interventions and community aspirations.

The community first needs to understand the status of their estuary, the long-term effects of the impacts of past stressors, and how to identify viable locations for recovery and restoration.

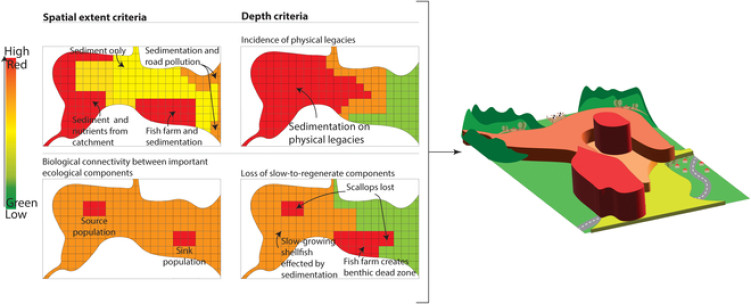

Local management agencies have information on current and future stressors on the estuary. The community also gathers local and indigenous knowledge of the catchment and the health of the estuary alongside monitoring data to identify changes in stressors, shellfish stocks, and habitats in the estuary. This information allows them to map the present spatial extent of the ecosystem response footprints and the magnitude of degradation.

Using this knowledge, community and marine managers identify stressors that are critical in setting the spatial extent of the response footprint, shellfish source populations, patchiness within the response footprint, and ecological connectivity across the estuary.

If the critical stressor, for example sediment, can be reduced and the depth of response footprint (the time for natural recovery to happen) is less than 10 years, then people can leave the ecosystem alone to recover itself.

If the time for natural recovery is greater than 10 years, for example if there are no external populations nearby, then an active restoration process of sourcing shellfish from elsewhere would be needed to help kick start the system again.

If areas are not physically suitable for natural recovery, then new locations need to be assessed. If a new, unimpacted location can’t be found, then the restoration process may need to involve manipulating habitats – this may be a human activity to create suitable environments or one that uses shellfish to change local processes, for example sediment resuspension.

The next stages in the process may include:

- monitoring the shellfish bed to support progress and to spread knowledge to other interested groups

- holding discussions between the community and governing bodies on how to improve overall estuarine health, for example large-scale riparian and coastal planting to reduce sediment and nutrients inputs from the area

- prioritising estuary health and connectivity when consenting for new activities.

This process of collaboration and co-development is likely to result in shared aspirations and goals that are more focused on improving the health of the estuary.

Information gathered by the community on the status of the estuary can be used to explore areas for natural recovery or active rehabilitation.

Opportunities for industry to work together

Jasmine says, the research has implications for industry and suggests working together to solve issues is the way forward — a cumulative fix for cumulative effects.

“It’s about thinking about the entirety of the ecosystem, not just specific species and managing just for that. We all need to be thinking about how everything has been impacted and not blaming one fishery or expecting one industry to solve the problem itself. It’s about working out what people need to do together”.

“We need to involve everyone on the entirety of the ecosystem to get targeted species back to, health. It's something that we all need to work towards fixing together.”

Clear footprints for next steps in research

This research complements other work of the Sustainable Seas Science Challenge because it helps kaitiaki and decision-makers act in a rapidly changing marine environment when people have to make decisions involving risk, uncertainty, and different ways of looking at the world.

Future projects are likely to offer tools for people to understand and communicate different perceptions of risk and uncertainty and how to use this understanding in decision-making. The ecosystem response footprint framework fits comfortably here and in the wider context of ecosystem-based management for healthy seas.