Posted on 13 May 2021

The ripple effects of research

- News

- Cumulative effects EBM in action Schools, education and communities Degradation and recovery Tangaroa Model Marlborough/Te Tauihu-o-te-waka

- 11 Minutes to read

There is no recipe book for managing cumulative effects in our estuaries and coasts. But earlier this year, our researchers and a crew of collaborators spent two weeks in the Marlborough Sounds gathering the information we need to meaningfully address the cumulative effects conundrum for managers and society.

As well as generating a slew of data, the field trip reconnected old friends, created new connections and sparked conversations that continue long after the North Island-based researchers have gone.

Building on past Sustainable Seas research into tipping points and ecosystem services, the Ecological responses to cumulative effects project team is developing new knowledge about cumulative effects – necessary to inform new tools and decision-making processes to help us better manage multiple stressors in our marine environment.

“Current tools for measuring cumulative effects just add up stressors, they don’t incorporate the multiple interactions between stressors and ecosystem responses. It is incredibly important that we understand how stressors might amplify or influence each other and how ecological responses change depending on the resilience of the ecosystems,” says Degradation and Recovery research theme leader Professor Conrad Pilditch (University of Waikato).

Collecting data from the seafloor is a team effort involving divers, scientists, skippers and local experts. Back boat (L-R): Simon Thrush, Eliana Ferratti, Stefano Schenone. Skipper Rob Davidson is straddling both boats. Front boat (L-R): Conrad Pilditch, Jen Hillman, Rebecca Gladstone-Gallagher, Johanna Gammal processing the samples the divers collected from the seafloor.

“We’re looking at some of the most critical stressors and examining their implications for change at a range of locations and habitat types, to build understanding of how stress effects ripple through ecosystems. This understanding will help build frameworks to assess the ecological footprints of stressors and inform risk assessments and planning strategies.”

The seafloor supports essential services

“It’s mission critical to understand how the seafloor works – it’s systems, processes and functions –deliver many of the ecosystem services that we rely on but often don’t care about until we lose them,” says project co-leader Professor Simon Thrush (University of Auckland).

“To progress our research, we need to measure critical ecosystem functions and how they vary across gradients of environmental stress. We also need to measure seafloor biodiversity to see how it responds and potentially recovers, to the cumulative effects of multiple stressors. This is intensive research and we need to develop new techniques to allow us to gather data faster and over larger areas.”

Traditional seafloor sampling typically involves measuring the number of animal species present. But recent research has demonstrated that measuring the animal’s activity from the tiny traces they leave on the sediment surface can inform us on changes in nutrient fluxes across the water-seafloor boundary. Changes in nutrients are important signals for ecosystem functions such as carbon processing and burial, removal of bio-available nitrogen.

To develop new ways of measuring how active the sediment-dwelling animals are in different communities and habitats, researchers sampled multiple sites around the Sounds. The main area they visited was the Outer Queen Charlotte Sounds where previous management actions such as the scallop fisheries closure and the marine reserve at Long Island, has offered some level of protection to the seafloor’s ecology.

Docked up at Ship Cove for a lunch break. Marlborough District Council provided the boat that carried the key sampling equipment. The row of trays on the stern are the benthic flux chambers (Credit: Conrad Pilditch).

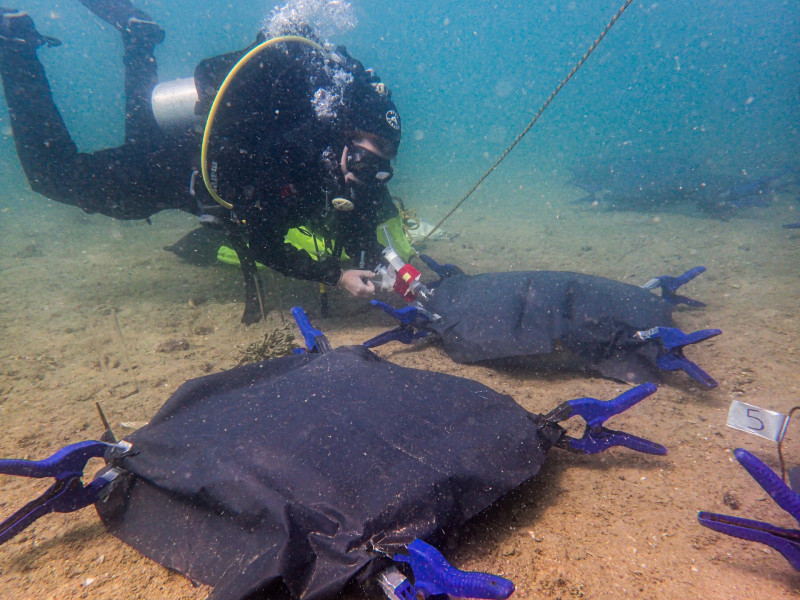

The project team ran experiments using benthic flux chambers, a key tool for measuring changes on the seafloor as it responds to different stressors.

Essentially metal frames, these chambers were pushed into the sediment and then sealed with a lid, allowing divers to take water samples from a contained environment. Any changes in water chemistry in the chamber indicate a positive or negative change. The chambers were left underwater on the seafloor for about 4 hours – enough time to detect any changes in oxygen, nitrogen and nutrient concentrations (the signal).

Research assistant Eliana Feretti (University of Auckland) sampling benthic flux chambers deployed in Otanerau Bay. The chambers are covered with black plastic to isolate the effect of photosynthesis from the other sedimentary biogeochemical processes. (Credit: Jen Hillman).

The data collected on this trip has been recreated as a series of digital terrain models (DTM) showing the changes in sediment microtopography in each chamber, a signal of animal activity which we can then link to the measured ecological functions.

Interactive map of the seafloor within one of the benthic chambers sampled at Otanerau Bay

This is a DTM, an interactive, 3D model of a soft-sediment sampling site in Otanerau Bay, part of East Bay. The dips and peaks you can see in this image are tubes, burrows and feeding mounds generated by the animals that live below the sediment surface and drive many important ecosystem services.

How to use the DTM: Click on the triangle button below to load the model. Click and hold the mouse to explore the seafloor. Scroll mouse wheel to zoom in/out. Created by Stefano Schenone (University of Auckland).

The project team will use DTM images like this to help inform the understanding about the ecological status of the different places they sampled in the Marlborough Sounds, and how that links to the provision of ecosystem services. They can help to investigate new rapid assessment techniques to support management and citizen science initiatives.

Why Marlborough Sounds?

Simon describes Marlborough Sounds as ecosystem-based management “in a nutshell”.

“The Sounds are a massive opportunity for everyone – from iwi, locals, to the Sustainable Seas Challenge, and all New Zealanders. It is the playground for the South Island and Wellingtonians. It’s a very special place where many different people, uses, values, activities, and conflicts co-exist, similar to the Hauraki Gulf.”

The Sounds also represents a diverse array of ecological habitats that provide a unique opportunity to study. It has only one marine reserve, but it allowed the researchers to sample across strong gradients - from protected sediments to areas that have been subjected to intensive scallop dredging in the past. The Sounds also contains a range of benthic protected areas to maintain seafloor biodiversity, as well as having destructive fishing banned from East Bay.

“This is a truly multi-use coastal ecosystem with areas of high conservation value, important aquaculture areas, many touristic uses and values all add to its significance for iwi. A place in need of EBM [ecosystem-based management] with all these values and uses in play, what a great opportunity for research!”

Local knowledge and collaboration is essential

Collaboration was at the heart of this field trip, with the Marlborough District Council providing the Harbourmaster’s facilities and boats for sampling and equipment storage

“[The Council] went out of their way to facilitate this trip. The active support from co-development partners and locals was vital to making the research happen,” says Conrad.

Marlborough District Council provided the Harbourmaster boat and skipper to transport the researchers and the equipment (Credit: Conrad Pilditch).

Rob Davidson – the skipper of the vessel – was one such local. “He’s a goldmine of local information. Rob knew what the weather would do, how the wind would come across the bays and what the currents would be like when,” says Simon. “Local knowledge was important for us North Islanders!”

Rob is also an environmental consultant who has worked in the Nelson and Marlborough regions for decades and has been central to the work of the Council in identifying benthic protection areas in the Sounds.

Contributing to the local community

In these times of economic recovery through Covid-19, marine research field trips to smaller communities like the Marlborough Sounds can be invaluable for local economies and communities.

“We estimated that this field trip contributed about $25,000 into the local economy. For dive shop operators and the accommodation providers, our visit was a much-appreciated shot in the arm,” says Conrad.

In addition to working with local community members, knowledge holders and generating local economic benefits, the field trip was a chance for the research team to reconnect with students and teachers from Marlborough Girls College.

Early on a Saturday morning, the team were joined by students and teachers from Marlborough Girls' College. The school chartered a local eco-tourism operator to take them to meet the researchers out on the water.

All aboard at Ships Cove. Tutanekai is the oldest commercial vessel in New Zealand. Owned and operated by Peter and Takutai Beech (Credit: Conrad Pilditch).

“For students to have the opportunity to see what marine researchers actually do is very special”, says Melynda Bentley, sustainability teacher. “Additionally, the girls saw emerging researchers in action – future role models of women working in marine science. That was not lost on them!”

Building on the connection developed between Melynda and her senior students with Simon and Conrad during earlier Sustainable Seas research, the school has recently introduced cross-curricular sustainability courses for juniors which incorporate EBM.

Led by Melynda and developed with input from other teachers, the junior course introduces years 9 and 10 to ecosystem-based management in the marine environment and the concept of ‘Ki uta ki tai – mountains to sea’. While the senior course for years 12 and 13 continues to teach environmental sustainability and incorporate ecosystem-based management and other concepts from Sustainable Seas research.

Rebecca Gladstone-Gallagher giving the students an impromptu lesson on sampling and sediment oxygen dynamics – what they were researching in the field that day and how they were doing. (Credit: Conrad Pilditch).

One of those concepts is ‘ecological footprints’ which Sustainable Seas researchers introduced to teachers in a workshop last year (an example of the ripple effect of the ongoing relationship between the school, community and Sustainable Seas researchers). Both courses are designed to help students learn to make informed management decisions of human activities on the land and under the water, using their knowledge of kaitiakitanga, mātauranga and ecosystem-based management.

Simon Thrush had just come up from a dive survey and was still in his dry suit but gave a great talk using footage of what the dive team had just been doing underwater. (Credit: Conrad Pilditch).

“The girls had never really thought about what’s actually living in and under the seafloor, or even realised that the seafloor is alive. They connected with the idea of life on the seafloor is not just seaweed and fish and that marine sediments play an important role in the marine ecosystem.

This trip reinforced the importance of getting students out of the classroom and into the field.”

Top (L-R): Simon Thrush, Jenny Pullin (Social Sci teacher) Helen Templeton (lab technician at MGC) Siobhan Keay (student), Conrad Pilditch, Melynda Bentley. Front (L-R): Students Eve Anderson, Leah Wearing, Molly Treloar, Zoe Luffman.

“One of the nicest things I heard all day was one of the students whose Dad is a biology teacher. It was his birthday and he said that is the best birthday present she could give him was to go on the trip and learn something”, says Conrad.

After the day on the water, the spin-off conversations that happened between the girls and their families helps to build awareness and capacity amongst the community (through conversations in community) and teaching the next generation of caretaker and researchers.

“The discussions afterwards were incredible. I was teaching ecology recently where one of the year 12s exclaimed “Oh, that’s what the Professors talked about!” So, they’re making those links, those connections long after the experience,” says Melynda.

They’re just getting started

It’s not just the Marlborough Sounds that needs ecosystem-based management and the research to support it. The project team is active around Aotearoa New Zealand (Hauraki Gulf, Ōhiwa Harbour, East Coast, Canterbury, Otago and Southland), working on finding out more about cumulative effects and the science needed to shift towards managing for recovery.

Collaboration with other Sustainable Seas research is key to the success of this project. For example, the team are working closely alongside with the team from Awhi Mai Awhi Atu with the aim of developing place-based tohu (indicators of change) – so that the management solutions are tailored to the people and place.

The field trip crew: (Top, L-R): the Harbourmaster, Stefano Schenone, Drew Lohrer, Eliana Ferratti, Rob Davidson, Simon Thrush. (Front, L-R): Rebecca Gladstone-Gallagher, Jen Hillman, Conrad Pilditch, Johanna Gammal (Credit: Conrad Pilditch).